| Question | Details |

|---|---|

| What led to the event? | … |

| What went wrong? | … |

| How/why did the barriers fail? | … |

| Who was involved in the event? [1] | … |

| Would the incident have occurred without this event? [2] | … |

| Is the event linked to a more general deficiency? [3] | … |

2. for multiple primary paths: would the incident have occurred IN THE MANNER DESCRIBED BY THIS ECF PATH without this event?

3. Is it part of a wider pattern? Are there any similarities with previous events during other incidents? Do different incidents begin to form a pattern of failure?

| Event | Contextual / Causal |

Justification |

|---|---|---|

| … | Contextual | Post-incident event. |

| … | Causal | The incident would not have happened if this had been avoided. |

| … | Causal (Barrier) | The incident would not have happened if this had been avoided. This represents a failed barrier because … |

| … | Contextual | Normal or intended behavior. |

| … | Causal | The incident would not have happened if this had been avoided. |

Requirements for Causal Findings

Representatives of the groups that support and implement a reporting system must participate in the identification of remedial actions. At the very least, they must consent to the implementation. Hence, it is important that the findings of any causal analysis are translated into a form that is readily accessible to those who must participate in and consent to the identification of recommendations in the aftermath of an incident.

1.Summarize the nature of the incident:- Explain 'when and where the error, material failure, or environmental factor occurred in the context of the accident sequence of events (e.g. while driving ambulance, during preop check)'

- Identify individuals who are involved by their duty position or name

- Components must be unambiguously denoted by a part or national stock number

- Any contributory environmental factors must also be described

The results of any causal analysis must be easy to understand by those without any formal training in the techniques that were used.

- For human error, identify the task or function the individual was performing and an explanation of how it was performed improperly. The "error" could be one of commission or omission e.g. individual performed the wrong task or individual incorrectly performed the right task

- For material failure, identify the mode of failure; e.g. corroded, burst, twisted, decayed etc.

- Identify the directive (i.e. SOP, guideline, pathway etc) or common practice governing the performance of the task or function

- Explain the consequences of the error / material failure / environmental effect:

- An error may directly result in damage to equipment or injury to personnel, or it may indirectly lead to the same end result

- A material failure may have an immediate effect on equipment or its performance, or it may create circumstances that cause errors resulting in further damage/injury inevitable

- Identify the reasons (failed control mechanisms) the human, material, environmental conditions caused or contributed to the incident. Give a brief explanation of how each reason contributed to the error, material failure, or environmental factor

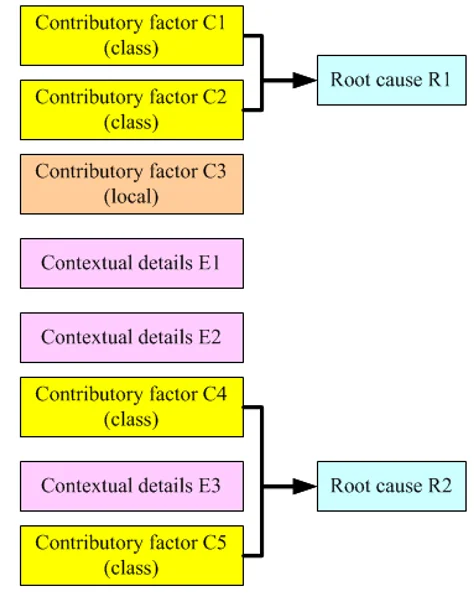

JCAHO uses a model which identifies proximal and distal causes. Others use particular and general causes, or primary and contributing causes. Irrespective of the precise model adopted, it is important to give some indication of the perceived importance of any particular causal finding. Example: 'The finding listed did not directly contribute to the causal factors involved in this incident; however, it did contribute to the (severity of injuries) or (incident damages()'.

4.Justify excluded factors:

It is also necessary to explain why particular 'causes' did NOT contribute to an adverse occurrence. The report must explain why recommendations do NOT address other aspects of the system. These excluded causes fall into TWO categories:

- Those factors that did not cause or exacerbate this incident but which have the potential to cause future failures if uncorrected

- Those factors that might have caused, or exacerbated, an incident but which were considered not to be relevant to this or future failures

Each cause-related finding must be substantiated. It can be difficult to follow why a secondary investigation was not initiated, or to identify the factors that led investigators to commit resources for computer-based simulations in one incident and not another. Similarly, it can be hard to understand why resources were not allocated to support a detailed causal analysis.

Scoping Recommendations

Causal findings help to guide the drafting of appropriate recommendations. This relationship is demonstrated by printing each finding next to the remedt that has "the best potential" for avoiding or mitigating the consequences of future incidents. Interventions must be pitched at the correct level. They must be detailed enough so that they avoid ambiguity. They must present the organisational, human factors and system details that are necessary if future incidents are to be avoided. They must not, however, be so specific that they fail to capture similar incidents that share some but not all of the causes of previous incidents.

- By time …

- By place …

- By function …

Conflicting Recommendations

- Different recommendations from similar incidents.

- Debate between investigators and higher-level administration.

- Correctives and extensions from safety managers.

Dangers of ambiguity.

From Causal Findings to Recommendations

There is a danger that investigators will continue to rely upon previous recommendations even though they have not proved to be effective in the past. Avoid arbitrary or inconsistent recommendations. Similar causal factors should be addressed by similar remedies. Of course, this creates tensions with the previous guidelines: the introduction of innovative solutions inevitably creates inconsistencies. The key point is that there should be some justification for treating apparently similar incidents in a different manner. These justifications should be documented together with any recommendations so that other investigators, line managers and regulators can follow the reasons why a particular remedy was proposed.

Different organizations have radically different approaches to the influence of financial or budgetary constraints on the identification of particular recommendations:

- 'should not allow the recommendation to be overly influenced by existing budgetary, material, or personnel restrictions' (e.g. Army): more open-ended, with the implicit acknowledgement that significant resources may be allocated if investment is warranted by a particular incident.

- 'more limited in which any recommendations, must target the doable' (e.g. hospitals): incident reporting is constrained to maximise the finite resources of the volunteer staff who run these systems.

A potential remedy must not introduce the possibility of new forms of failure into the system. This is easier to state than to achieve: new forms of working may have subtle effects, and the safety-related consequences may only become obvious many months later.

The relatively low frequency of many adverse occurrences makes it difficult to determine whether recommendations have any effect. Hence, there is a danger that the justification for any recommendation will be challenged.

Incidents seldom occur in exactly the same manner. Recommendations must be proof against these small differences, and must be applicable within a range of local working environments. This is usually achieved by drafting guidelines at a relatively high-level of abstration; if guidelines are too context specific then it can be difficult for safety managers to identify how to apply the guidelines to their own working environment.

Recommendations are typically made to the statutory body that commissions the work. These statutory organizations must then either accept the recommendations or explain the reasons why they choose to reject them. There, it is important that any recommendations are well supported by the products of causal analysis. If a recommendation is accepted, the statutory body must ensure that it is implemented. There are occasions when investigators must identify who will be expected to satisfy a requirement.

| Causal Factor | Justification |

|---|---|

| The explosives team leader failed to turn in excess explosive material to the ammunition supply point. | The incident would not have happened if the bag containing the additional M14 initiation system and detonating cord had been handed in. |

| The administration batalion (operations, planning, and training officer) recognised but failed to stop the deviated and unpracticed operation. | The incident might not have occured if they had intervened more directly when their question about the bag went unanswered. |

| Marking team leader took up hide position closer than the authorised 50 meters from the explosives site. | The consequences of the incident might have been significantly reduced if they had been further from the detonation site. |

References:

- C.W. Johnson, Failure in Safety-Critical Systems: A Handbook of Accident and Incident Reporting. University of Glasgow Press, Glasgow, Scotland, October 2003. www.dcs.gla.ac.uk/~johnson/book/

- Wikipedia. Mars Climate Orbiter. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Accessed March 7,1997.