Error Classification

Errors

An error is the failure of planned actions to achieve the desired goal.

- Execution: The plan is adequate, but the associated actions do not go as intended. Occur during the largely automatic performance of some routine task, usually in familiar surroundings.

- Slips: observable actions, associated with attention failures.

- Lapses: more interal events, relate to failures of memory.

- Planning: The action may go entirely as planned, but the plan is inadequate to achieve its intended outcome.

- Mistakes: failures of intention. The failure lies at a higher level; the mental processes involved in planning, formulating intentions, judging, problem solving.

- Rule-based mistakes: relate to problems for which the person possesses some prepackaged solution, acquired as the result of training or experience. The errors come in various forms:

- misapplication of a good rule (usually because of a failure to spot the contra-indications)

- application of a bad rule

- non-application of a good rule

- Knowledge-based mistakes: occur in novel situations where the solution to a problem has to be worked out on the spot without the help of preprogrammed solutions. The human mind is subject to confirmation bias or "mindset"

- Rule-based mistakes: relate to problems for which the person possesses some prepackaged solution, acquired as the result of training or experience. The errors come in various forms:

- Mistakes: failures of intention. The failure lies at a higher level; the mental processes involved in planning, formulating intentions, judging, problem solving.

Violations

A violation is a deliberate deviation from safe operating practices, procedures, standards, or rules. The actions (though not the possible bad consequences) were intended.

- Routine violations: cutting corners whenever possible

- Optimising violations: Actions taken to further personal rather than strictly task related goals (that is, for "kicks" or to alleviate boredom)

- Necessary or situational violations: seem to offer the only way to getting the job done, and where the rules or procedures are seen to be inappropriate for the present situation.

Errors vs Violations

Errors

- Arise primarily from informational problems (forgetting, inattention, incomplete knowledge)

- Explained by what goes on in the mind of an individual

- Can be reduced by improving the quality and the delivery of necessary information within the workplace

Violations

- More generally associated with motivational problems (low morale, poor supervision, perceived lack of concern, failure to reward compliance and sanction non-compliance)

- Occur in a regulated social context

- Require motivational and organisational remedies

Active or Latent Factors

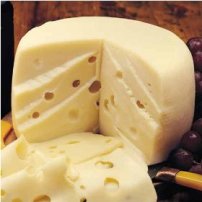

This approach to the genesis of human error was proposed by James Reason (1990). [James Reason] Generally referred to as the "Swiss cheese" model of human error, it describes four levels of human failure, each influencing the next. According to this metaphor, in a complex system, hazards are prevented from causing human losses by a series of barriers. Each barrier has unintended weaknesses or holes — hence the similarity with Swiss cheese. These weaknesses are inconstant i.e. the holes open and close at random. When by chance all holes are aligned, the hazard reaches the patient and causes harm. This model draws attention to the health care system, as opposed to the individual, and to randomness, as opposed to deliberate action, in the occurrence of medical errors.

- Active failures: Unsafe Acts (errors and violations) committed by those at the "sharp end" of the system (surgeons, anesthetists, nurses, physicians, etc). It is the people at the human system interface whose actions can, and sometimes do, have immediate adverse consequences. Active failures are represented as "holes" in the cheese.

- Latent failures: latent failures are created as the result of decisions, taken at the higher echelons of an organisation. Their damaging consequences may lie dormant for a long time, only becoming evident when they combine with local triggering factors to breach the system's defences.

- Preconditions for Unsafe Acts: This level involves conditions such as mental fatigue and poor communication and coordination practices. If fatigued staff fail to communicate and coordinate their activities with others in the hospital or individuals external to the hospital (e.g. local department of health, national health bureau etc) poor decisions are made and errors often result.

- Unsafe Supervision: But exactly why did communication and coordination break down in the first place? In many instances, the breakdown of good CRM practices can be traced back to this third level of human failure. If, for example, two inexperienced (and perhaps even below average) nurses are paired with each other and sent to transport a seriously ill patient to a department in another part of the hospital, is anyone really surprised by a tragic outcome? If this questionable staffing practice is coupled with the lack of quality staff training, the potential for miscommunication and medical errors is magnified. In a sense then, the staff was "set up" for failure. This is not to lessen the role played by the staff, only that intervention and mitigation strategies might lie higher within the system.

- Organizational Influences: Reason's model did not stop at the supervisory level; the organization itself can affect performance at all levels. For instance, in times of fiscal austerity, funding is often cut, and as a result, training and ward orientation are curtailed. Consequently, supervisors are often left with no alternative but to ask "non-proficient" nurses with to do complex tasks. Not surprisingly then, in the absence of good training, communication and coordination failures will begin to appear as will a myriad of other preconditions, all of which will affect performance and elicit staff errors.

The difference between active and latent errors is made by considering two aspects: the time from the error to the manifestation of the adverse event, and two, where in the system did the error occur.

Unsafe Acts

Errors: mental or physical activities of individuals that fail to achieve their intended outcome.Since human beings by their very nature make errors, these unsafe acts dominate most accident databases.

- Skill-Based Errors

- Attention Failures (slips): linked to many skill-based errors such as the breakdown in visual scan patterns, task fixation, the inadvertent activation of controls, and the misordering of steps in a procedure. These attention failures commonly occur during highly automatized behavior.

A classic example is an aircraft crew that becomes so fixated on trouble-shooting a burned out warning light that they do not notice their fatal descent into the terrain. Or a person who locks himself out of the car or misses his exit on the highway because he was distracted, in a hurry, or daydreaming. - Memory Failures (lapses): often appear as omitted items in a checklist, place losing, or forgotten intentions. For example, most of us have experienced going to the refrigerator only to forget what we went for. Likewise, it is not difficult to imagine that when under stress during emergencies, critical steps in emergency procedures can be missed. However, even when not particularly stressed, individuals have forgotten to do basic steps in common procedures e.g. leaving the garage door open after parking the car — at a minimum, an embarrassing gaffe.

- Attention Failures (slips): linked to many skill-based errors such as the breakdown in visual scan patterns, task fixation, the inadvertent activation of controls, and the misordering of steps in a procedure. These attention failures commonly occur during highly automatized behavior.

- Decision Errors:intentional behavior that proceeds as intended, yet the plan proves inadequate or inappropriate for the situation. Often referred to as "honest mistakes", these unsafe acts represent the actions or inactions of individuals whose "hearts are in the right place", but they either did not have the appropriate knowledge or just simply chose poorly. Perhaps the most heavily investigated of all error forms, decision errors can be grouped into three general categories:

- procedural decision errors (Orasanu, 1993) or rule-based mistakes (Rasmussen, 1982): occur during highly structured tasks of the sort: if X then do Y. Medicine, particularly with guidelines and clinical pathways, is highly structured, and consequently, much of decision making is procedural. There are very explicit procedures to be performed at virtually all phases. Still, errors can, and often do, occur when a situation is either not recognized or misdiagnosed, and the wrong procedure is applied. This is particularly true when medical staff are placed in highly time-critical emergencies like performing CPR for a patient being transported in corridors and elevators.

- choice decision errors (Orasanu, 1993) or knowledge-based mistakes (Rasmussen, 1986): not all situations have corresponding procedures to deal with them and hence a choice has to be made from multiple response options. This type of error is particularly common when there is insufficient experience, time, or other outside pressures that may preclude correct decisions.

- problem solving errors: occur when a problem is not well understood, and formal procedures and response options are not available. During these ill-defined situations the invention of a novel solution is required. In a sense, individuals find themselves where no one has been before. Individuals placed in this situation must resort to slow and effortful reasoning processes where time is a luxury rarely afforded. This type of decision making is more infrequent then other forms, but the relative proportion of problem-solving errors committed is markedly higher.

- Perceptual Errors: When one's perception of the world differs from reality, errors can, and often do, occur. Typically, perceptual errors occur when sensory input is degraded or "unusual". Visual illusions, for example, occur when the brain tries to "fill in the gaps" with what it feels belongs in a visually impoverished environment, like that seen at night. Likewise, spatial disorientation occurs when the vestibular system cannot resolve one's orientation in space and therefore makes a "best guess" — typically when visual (horizon) cues are absent. The unsuspecting individual is left to make a decision that is based on faulty information and the potential for committing an error is elevated. It is important to note, however, that it is not the illusion or disorientation that is classified as a perceptual error. Rather, it is the staff person's erroneous response to the illusion or disorientation.

Violations: willful disregard for the rules and regulations that govern safety.

- Routine: tend to be habitual by nature and often tolerated by governing authority. Consider, for example, the individual who drives consistently 5-10 mph faster than allowed by law. While he is certainly against the governing regulations, many others do the same thing. Furthermore, individuals who drive 64 mph in a 55 mph zone, almost always drive 64 in a 55 mph zone. That is, they "routinely" violate the speed limit. What makes matters worse, these violations (commonly referred to as "bending" the rules) are often tolerated and, in effect, sanctioned by supervisory authority (i.e., you're not likely to get a traffic citation until you exceed the posted speed limit by more than 10 mph). If, however, the local authorities started handing out traffic citations for exceeding the speed limit on the highway by 9 mph or less (as is often done on military installations), then it is less likely that individuals would violate the rules. Therefore, by definition, if a routine violation is identified, one must look further up the supervisory chain to identify those individuals in authority who are not enforcing the rules.

- Exceptional: isolated departures from authority, not necessarily indicative of individual's typical behavior pattern nor condoned by management (Reason, 1990). For example, an isolated instance of driving 105 mph in a 55 mph zone is considered an exceptional violation. However, it is important to note that, while most exceptional violations are appalling, they are not considered "exceptional" because of their extreme nature. Rather, they are considered exceptional because they are neither typical of the individual nor condoned by authority. Still, what makes exceptional violations particularly difficult for any organization to deal with is that they are not indicative of an individual’s behavioral repertoire and, as such, are particularly difficult to predict.

Preconditions

Substandard Conditions of Operators:

- Adverse Mental States: mental conditions that affect performance; e.g.loss of situational awareness, task fixation, distraction, and mental fatigue due to sleep loss or other stressors. If an individual is mentally tired for whatever reason, the likelihood increase that an error will occur. In a similar fashion, overconfidence and other attitudes such as arrogance and impulsivity will influence the likelihood that a violation will be committed.

- Adverse Physiological States: medical or physiological conditions that preclude safe operations. Conditions such as visual illusions and spatial disorientation as described earlier, as well as physical fatigue, and the myriad of pharmacological and medical abnormalities known to affect performance. Often overlooked are the effects on performance of simply being ill. Nearly all of us have gone to work ill, dosed with over-the-counter, antihistamines, acetaminophen, and other non-prescription pharmaceuticals thinking little of the side-effects of antihistamines, fatigue, and sleep loss on decision-making.

- Physical/Mental Limitations: refers to those instances when mission requirements exceed the capabilities of the individual at the controls. For example, the human visual system is severely limited at night; yet, like driving a car, drivers do not necessarily slow down or take additional precautions. Similarly, there are occasions when the time required to complete a task exceeds an individual's capacity. It is well documented that if individuals are required to respond quickly (i.e., less time is available to consider all the possibilities or choices thoroughly), the probability of making an error goes up markedly. In addition, should consider if involved individuals are simply are not compatible with the job, because they are either unsuited physically or do not possess the mental ability or aptitude.

Substandard Practices of Operators:

- Staff Resource Mismanagement: The category of staff resource mismanagement was created to account for occurrences of poor coordination among personnel. This includes coordination both within and between departments, as well as with other support personnel as necessary. It also includes coordination before and after procedures (e.g. surgical operation, hospital accreditation) with briefing and debriefing of the staff.

- Personal Readiness: Individuals are expected to show up for work ready to perform at optimal levels. Nevertheless, personal readiness failures occur when individuals fail to prepare physically or mentally for duty. For instance, violations of staff rest requirements and self-medicating will affect performance on the job. When individuals violate rest requirements, they run the risk of mental fatigue and other adverse mental states, which ultimately lead to errors and accidents. Note however, that violations that affect personal readiness are not considered "unsafe act, violation" since they typically do not happen at work, nor are they necessarily active failures with direct and immediate consequences.

Still, not all personal readiness failures occur as a result of violations of governing rules or regulations. For example, running 10 miles before coming to work may not be against any existing regulations, yet it may impair the physical and mental capabilities of the individual enough to degrade performance and elicit unsafe acts. Likewise, the traditional "candy bar and coke" lunch of the modern young person may sound good but may not be sufficient to sustain performance in the rigorous environment of a hospital. While there may be no rules governing such behavior, hospital staff must use good judgment when deciding whether they are "fit" to come to work.

Unsafe Supervision

Inadequate Supervision: The role of any supervisor is to provide the opportunity to succeed.

To do this, the supervisor, no matter at what level of operation, must provide guidance, training opportunities, leadership, and motivation, as well as the proper role model to be emulated.

Unfortunately, this is not always the case.

Also, sound professional guidance and oversight is an essential ingredient of any successful organization.

While empowering individuals to make decisions and function independently is certainly essential, this does not divorce the supervisor from accountability.

The lack of guidance and oversight has proven to be the breeding ground for many of the violations that have crept into routine procedures. As such, any thorough investigation of accident causal factors must consider the role supervision plays (i.e., whether the supervision was inappropriate or did not occur at all) in the genesis of human error.

- Failed to provide guidance

- Failed to provide operational doctrine

- Failed to provide oversight

- Failed to provide training

- Failed to track qualifications

- Failed to track performance

Planned Inappropriate Operations: Occasionally, the operational tempo and/or the scheduling of staff is such that individuals are put at unacceptable risk, staff rest is jeopardized, and ultimately performance is adversely affected.

Such operations, though arguably unavoidable during emergencies, are unacceptable during normal operations.

Take, for example, the issue of improper staff pairing.

It is well known that when very senior, dictatorial staff are paired with very junior, weak personnel, communication and coordination problems are likely to occur.

- Failed to provide correct data

- Failed to provide adequate briefing time

- Improper staffing (not enough)

- Mission not in accordance with rules/regulations

- Provided inadequate opportunity for staff to rest

Failed to Correct Problem: when deficiencies among individuals, equipment, training or other related safety areas are "known" to the supervisor, yet are allowed to continue unabated.

For example, it is not uncommon for accident investigators to interview the friends, colleagues, and supervisors after a hospital incident only to find out that they "knew it would happen some day".

If the supervisor knew that a surgeon was incapable of operating safely, and allowed the doctor to operate anyway, the failure to correct the behavior, either through remedial training or, if necessary, cancellation of the operating theatre privilege, essentially signed the patient's death warrant.

Likewise, the failure to consistently correct or discipline inappropriate behavior fosters an unsafe atmosphere and promotes the violation of rules.

- Failed to correct document in error

- Failed to identify an at-risk surgeon

- Failed to initiate corrective action

- Failed to report unsafe tendencies

Supervisory Violations: on the other hand, are reserved for those instances when existing rules and regulations are willfully disregarded by supervisors. Although arguably rare, supervisors have been known occasionally to violate the rules and doctrine when managing their assets. For instance, there have been occasions when individuals (e.g. nurse physician assistant) were permitted to perform an operation without current qualifications or license. Likewise, it can be argued that failing to enforce existing rules and regulations or flaunting authority are also violations at the supervisory level. While rare and possibly difficult to cull out, such practices are a flagrant violation of the rules and invariably set the stage for the tragic sequence of events that predictably follow.

- authorized unnecessary hazard

- Failed to enforce rules and regulations

- Authorized unqualified personnel to operate

Organizational Influences

Resource Management: This category encompasses the realm of corporate-level decision making regarding the allocation and maintenance of organizational assets such as human resources (personnel), monetary assets, and equipment/facilities. Generally, corporate decisions about how such resources should be managed center around two distinct objectives — the goal of safety and the goal of on-time, cost-effective operations. In times of prosperity, both objectives can be easily balanced and satisfied in full. However, there may also be times of fiscal austerity that demand some give and take between the two. Unfortunately, history tells us that safety is often the loser in such battles and safety and training are often the first to be cut in organizations having financial difficulties. If cutbacks in such areas are too severe, proficiency may suffer, and the best staff may leave the organization for greener pastures.

- Human Resources

- Selection

- Staffing

- Training

- Monetary / budget resources

- Excessive cost cutting

- Lack of funding

- Equipment / facility resources

- Poor design

- Purchasing of unsuitable equipment

Excessive cost-cutting could also result in reduced funding for new equipment or may lead to the purchase of equipment that is sub optimal and inadequately designed for the type of procedures performed in that hospital. Other trickle-down effects include poorly maintained equipment and workspaces, and the failure to correct known design flaws in existing equipment. The result is a scenario involving unseasoned, less-skilled staff using old and poorly maintained equipment under the least desirable conditions and schedules.

Organizational Climate: refers to a broad class of organizational variables that influence worker performance.

In general, it can be viewed as the working atmosphere within the organization.

One telltale sign of an organization's climate is its structure, as reflected in the chain-of-command, delegation of authority and responsibility, communication channels, and formal accountability for actions.

If management and staff within an organization are not communicating, or if no one knows who is in charge, organizational safety clearly suffers and accidents happen.

An organization's policies and culture are also good indicators of its climate.

Policies are official guidelines that direct management's decisions about such things as hiring and firing, promotion, retention, raises, sick leave, drugs and alcohol, overtime, accident investigations, and the use of safety equipment.

Culture, on the other hand, refers to the unofficial or unspoken rules, values, attitudes, beliefs, and customs of an organization.

Culture is "the way things really get done around here".

When policies are ill-defined, adversarial, or conflicting, or when they are supplanted by unofficial rules and values, confusion abounds within the organization.

Indeed, there are some corporate managers who are quick to give "lip service" to official safety policies while in a public forum, but then overlook such policies when operating behind the scenes.

Safety is bound to suffer under such conditions.

- Structure

- Chain-of-command

- Delegation of authority

- Communication

- Formal accountability for actions

- Policies

- Hiring and firing

- Promotion

- Drugs and alcohol

- Culture

- Norms and rules

- Values and beliefs

- Organizational justice

Organizational Process: This category refers to corporate decisions and rules that govern the everyday activities within an organization, including the establishment and use of standardized operating procedures and formal methods for maintaining checks and balances (oversight) between the workforce and management. For example, such factors as operational tempo, time pressures, incentive systems, and work schedules are all factors that can adversely affect safety. There may be instances when those within the upper echelon of an organization determine that it is necessary to increase the operational tempo to a point that overextends a supervisor's staffing capabilities. Therefore, a supervisor may resort to the use of inadequate scheduling procedures that jeopardize staff rest and produce sub optimal staff pairings, putting personnel at an increased risk of a mishap. However, organizations should have official procedures in place to address such contingencies as well as oversight programs to monitor such risks.

- Operations

- Operational tempo

- Time pressure

- Production quotas

- Incentives

- Measurement / appraisal

- Schedules

- Deficient planning

- Procedures

- Standards

- Clearly defined objectives

- Documentation

- Instructions

- Oversight

- Risk management

- Safety programs

References:

- Reason J. The human contribution: unsafe acts, accidents and heroic recoveries. Ashgate Publishing Limited, Surrey, England. 2008

- Carson M. The human factors analysis and classification system — HFACS. www.coloradofirecamp.com Colorado Firecamp.