The PDSA method follows a four stage cyclic learning approach to adapt changes aimed at improvement. In the "plan" stage a change aimed at improvement is identified, the "do" stage sees this change tested, the "study" stage examines the success of the change and the "act" stage identifies adaptations and next steps to inform a new cycle. [Table 1]

The principle of cycles is to promote the use of a small-scale, iterative approach to test changes, as this:

- provides users with freedom to act and learn

- minimizes risk to patients

- minimizes resources required

- enables rapid assessment and provides flexibility to adapt the change according to feedback to ensure fit-for-purpose solutions are developed.

- provides the opportunity to build evidence for the change being tested

- increases stakeholders participation confidence in the intervention increases

Key metrics indicating successful use of the PDSA method: [Table 2]

- initial small-scale testing

- prediction-based testing of change

- use of iterative cycles

- short duration of cycles (less than a month)

- detailed documentation

- use of data over time (run charts, CUSUM control charts)

The PDSA cycle promotes prediction of the outcome of a test of change and subsequent measurement over time (quantitative or qualitative) to assess the impact of that intervention on the process or outcomes of interest. Thus, learning is the primary goal (not improvement). In complex settings with inherent variability, measurement of data over time helps understand natural variation in the system, and increases awareness of other factors influencing processes or outcomes.

- Plan

-

Identify objective

Identify questions and predictions

Plan to carry out the cycle (who, when, where, when) - Do

-

Execute the plan

Document problems and unexpected observations

Begin data analysis - Study

-

Complete the data analysis

Compare data to predictions

Summarise what was learnt - Act

-

What changes are to be made?

What will the next cycle entail? (Adopt/Adapt/Abandon)

|

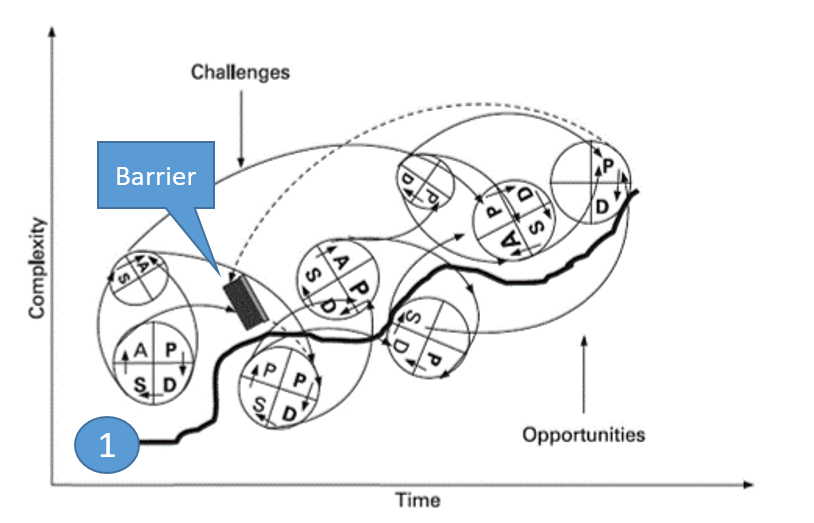

Figure 1. Ramp model of PDSA improvement.

|

However, this pristine view of PDSA does not capture reality, which involves frequent ‘false starts, miss firings, plateaus, regroupings, backsliding, feedback, and overlapping scenarios within the process.’ [Figure 2] depicts a complex network which is a tangle of the numerous starts, stops, backtracking and, often incomplete, cycles of change that occur in practice. Even so, the changes continue to move upwards, to better performance (Thick black line ① in Figure 2).

Table 2 Theoretical framework based on key features of the plan–do–study–act (PDSA) cycle method

| Feature of PDSA | Description of feature | How this was measured |

|---|---|---|

| Iterative cycles | To achieve an iterative approach, multiple PDSA cycles must occur. Lessons learned from one cycle link and inform cycles that follow.Depending on the knowledge gained from a PDSA cycle, the following cycle may seek to modify, expand, adopt or abandon a change that was tested |

Were multiple cycles used? Were multiple cycles linked to one another (ie, does the "act" stage of one cycle inform the "plan" stage of the cycle that follows)? When isolated cycles were used were future actions postulated in the "act"stage? |

| Prediction-based test of change | A prediction of the outcome of a change is developed in the "plan" stage of a cycle. This change is then tested and examined by comparison of results with the prediction. |

Was a change tested? Was an explicit prediction articulated? |

| Small-scale testing | As certainty of success of a test of change is not guaranteed, PDSAs start small in scale and build in scale as confidence grows. This allows the change to be adapted according to feedback, minimises risk and facilitates rapid change and learning. |

Sample size per cycle? Temporal duration of cycles? Number of changes tested per cycle? Did sequential cycles increase scale of testing? |

| Use of data over time | Data over time increases understanding regarding the variation inherent in a complex healthcare system. Use of data over time is necessary to understand the impact of a change on the process or outcome of interest. |

Was data collected over time? Were statistics used to test the effect of changes and/or understand variation? |

| Documentation | Documentation is crucial to support local learning and transferability of learning to other settings. |

How thoroughly was the application of the PDSA method detailed in the reports? Was each stage of the PDSA cycles documented? |

References

- Ogrinc G, Shojania KG. Building knowledge, asking questions. qualitysafety.bmj.com BMJ Qual Saf 2014; 23: 265-2671-3.

- Reed JE, Card AJ. The problem with Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles qualitysafety.bmj.com BMJ Qual Saf 2016; 25: 147-152.

- Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, Darzi A, Bell D, Reed JE. Systematic review of the application of the plan-do-study-act method to improve quality in heatlthcare qualitysafety.bmj.com BMJ Qual Saf 2014; 23: 290-298.

- Leis JA, Shojania KG. A primer on PDSA: executing plan-do-study-act cycles in practice, not just in name qualitysafety.bmj.com BMJ Qual Saf 2017; 26: 572-577.

- Etchells E, Ho M, Shojania KG. Value of small sample sizes in rapid-cycle quality improvement projects qualitysafety.bmj.com BMJ Qual Saf 2016; 25(3): 202-206.

- Etchells E, Woodcock T. Value of small sample sizes in rapid-cycle quality improvement projects 2: assessing fidelity of implementation for improvement interventions qualitysafety.bmj.com BMJ Qual Saf 2018; 7(1): 61-65.

- Perla RJ, Provost LP, Murray SK. Sampling considerations for health care improvement qualitysafety.bmj.com Qual Manag Health Care 2013; 22(1): 36-47.

- Perla RJ, Provost LP. Judgment sampling: a health care improvement perspective. qualitysafety.bmj.com Qual Manag Health Care 2012; 20(3): 170-176.